Some Babies Come With Instructions

|

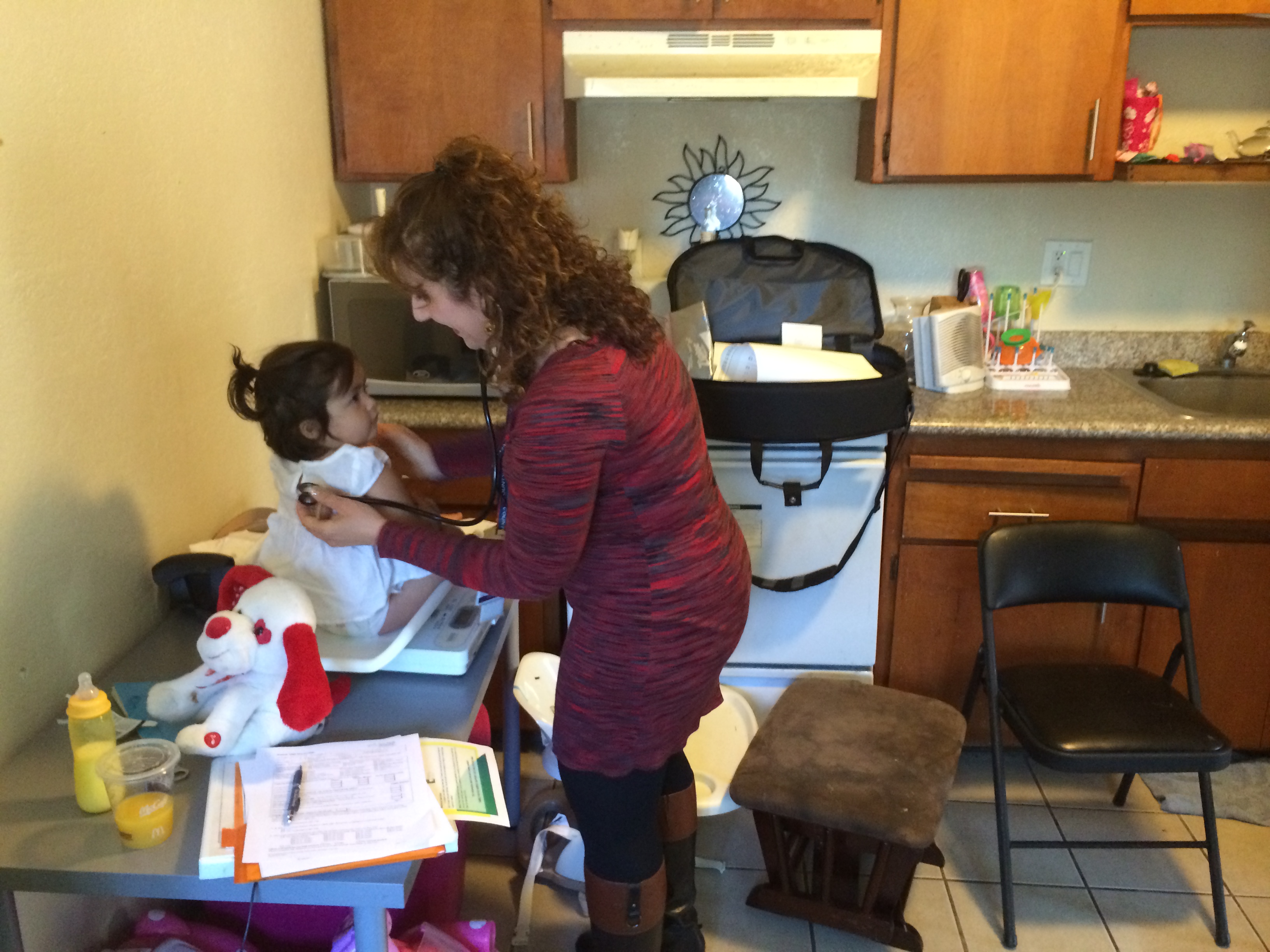

First-time parents Rebecca and Sergio live with their toddler daughter, Iliana, in a tiny apartment in the shadow of an Oakland freeway. Early in the pregnancy they sought help to become better parents than their own had been for them. Since before Iliana even was born a nurse from the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency has visited the couple’s home twice a month to answer questions, give advice and check the little girl’s development. Using funding from the BSCC’s Proud Parenting grant available to help vulnerable new moms and dads who have been jailed or in foster care, Amennah Moghaddam monitors Iliana’s development and offers ongoing counseling to help the couple raise a vibrant and healthy daughter. Referrals to the program come from the Probation Department and community. The goals are to break the intergenerational cycle of violence, provide young parents with basic parenting skills and therefore increase the chances the child will grow up outside of “the system.”

|

“She gives good advice,” Rebecca says. “I wouldn’t have breast fed for as long as I did without her encouragement.” Moghaddam has urged the parents to read to their baby since her birth. She measures Iliana’s weight weekly and cautions against juice to avoid tooth decay and sugary calories, even though it is a part of the toddler’s WIC package. At a recent visit she advised that Iliana, at 15 months, should start playing with blocks to build dexterity and motor skills, at 16-18 months they will notice her sharing and looking for validation from her parents. The Alameda County program is modeled on 35-year-old national Nurse-Family Partnership, which has collected national evidence to show that its benefits are multi-generational. The partnership reports: • A 48 percent reduction in child abuse and neglect. • A 56 percent reduction in ER visits for accidents

|

• A 59 percent reduction in arrests by age 15 • A 67 percent reduction by age 6 of child behavioral and intellectual problems. Moghaddam is like a part of the young family, and will be until Iliana turns two. She is greeted on her visits with hugs, and acts like a mother to all three family members, directing them to bus vouchers, clothes and family events that they all can attend. She inquires about Rebecca’s plans to return to school, and even looks for ways to make their apartment near a freeway healthier for all of them. “We can get filters from the American Lung Association’s kick asthma program,” she says. At every visit Moghaddam arrives with a menu of topics, each with handouts that go with it. At a recent visit the parents reported that Iliana had fallen out of a chair. They want Moghaddam to make sure their home is safe and to teach them how to be aware of potential dangers. She starts offering advice right away. Don’t put ice on a burn or it will stick to it. Is there a gun in the house? “Yes, but I know to keep the bullets separate,” Sergio says. The nurse tells them that on the next visit she will bring a CPR doll.

|

“The parents look forward to the visits. Once a week seems like a lot, but more than once a week you have a question,” Sergio said. They believe the guidance will pay off. “I want her to have a better life than what I had,” Rebecca said as she picked up her baby to give a hug. “That keeps me motivated to follow through on her advice. I want her to have parents with careers because I don’t want her to be afraid that we won’t have money.”