“It’s so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Sheriff Leroy Baca of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Jan. 16, 2014. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn,” inmate Solomon Brown, 30. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes,” Lt. Joseph Badali.

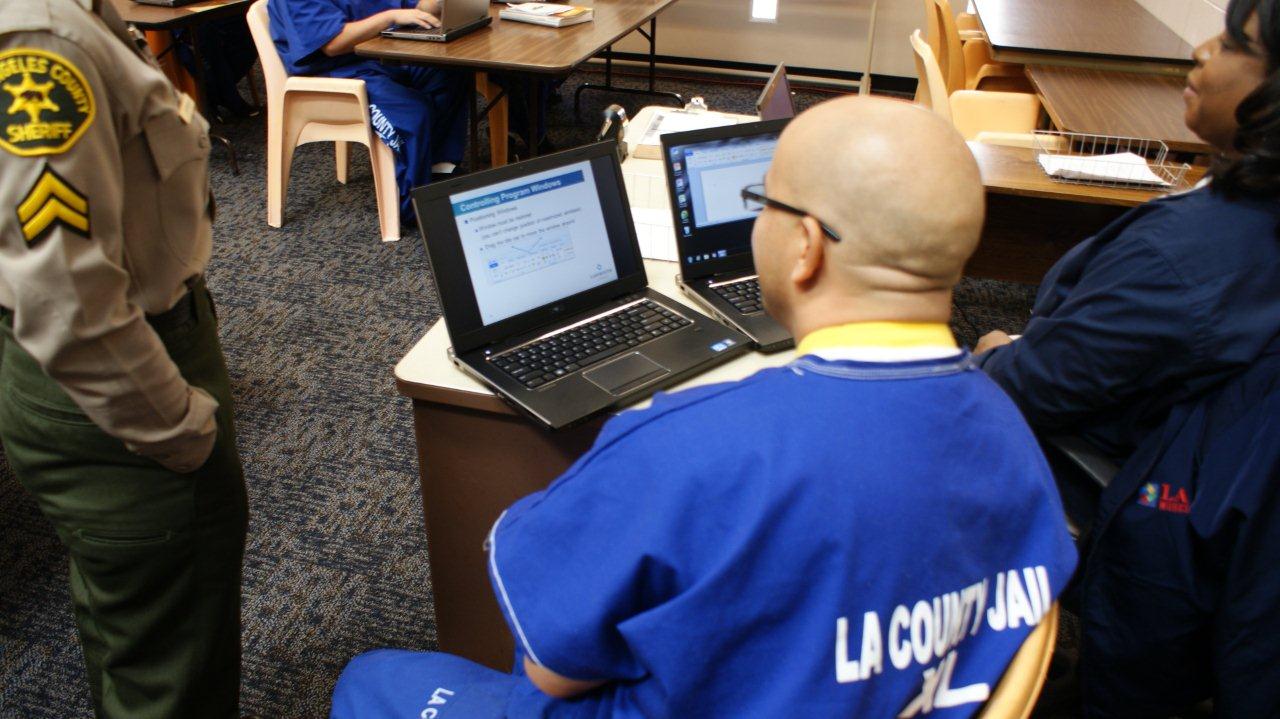

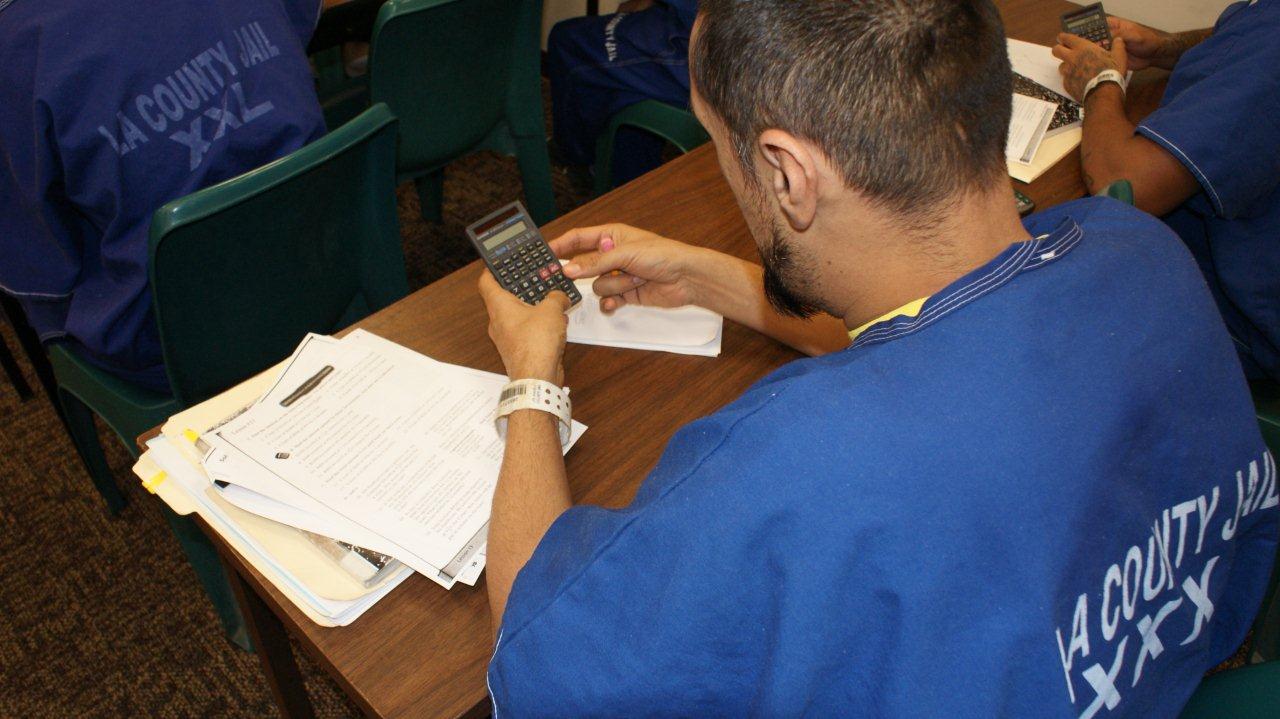

“It’s so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Sheriff Leroy Baca of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Jan. 16, 2014. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn,” inmate Solomon Brown, 30. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes,” Lt. Joseph Badali. As women in blue scrubs gather around tables in the Los Angeles County Twin Towers Jail, 45-year-old Anna Maria Gonzalez cracks open a workbook and begins to write. The mother of three grown children left school in Mexico in the sixth grade. She was unable to comprehend written English when she began serving five years for possession of drugs for sale. Now she’s on her way to earning a high school diploma in a cafeteria converted into a classroom. “I feel privileged to be here in this class,” she said. “I heard they didn’t have classes here like this before, and that would be a waste of time for everybody.” In 2011 the Governor’s public safety realignment strategy meant low-level, non-violent offenders and parole violators would serve their terms in county jails, closer to support systems and evidence-based rehabilitative programming designed by officials of the state’s 58 counties. Then-Sheriff Leroy Baca was challenged to find ways to manage thousands of inmates while helping them end the cycle of crime in which many of them where caught. He believes that education is key to ending or slowing recidivism, but when jails held offenders an average of 45 days before sending them to state prisons there wasn’t much he could do. Realignment inspired Baca in 2012 to create a new bureau in his department called Education Based Incarceration (subtitled Creating a Life Worth Living) and he placed Brantley Choate, PhD, in charge of curriculum, and made Capt. Michael Bornman head of the unit. They viewed education as a means for dealing with the tougher caliber of prisoner who could be serving years — instead of weeks — in local jails. “The nature of crime is extraordinarily complex, but education is not complex,” Baca said. “It’s the tool that has advanced civilization from the Dark Ages to now.” The LA jail system contracts with three charter schools to teach inside the six facilities. About 3,000 of the 19,000 inmates housed in the nation’s most populous county jail complex are enrolled in degree and trade programs. The charter schools are funded by the state based on Average Daily Attendance, and costs of the vocational and Life Skills courses are covered by the Inmate Welfare Fund. Teacher Arnold Gamboa trains inmates in basic computer concepts through the New Opportunities Charter School, which is part of the local Centinela Valley Union High School District. He entered the education field as an elementary school teacher but prefers working with his current students. “To see them excited over something they’ve learned is very satisfying to me,” Gamboa said. “I love for them to set a short-term goal in this class and then say to me ‘Mr. Gamboa, I did it!’”

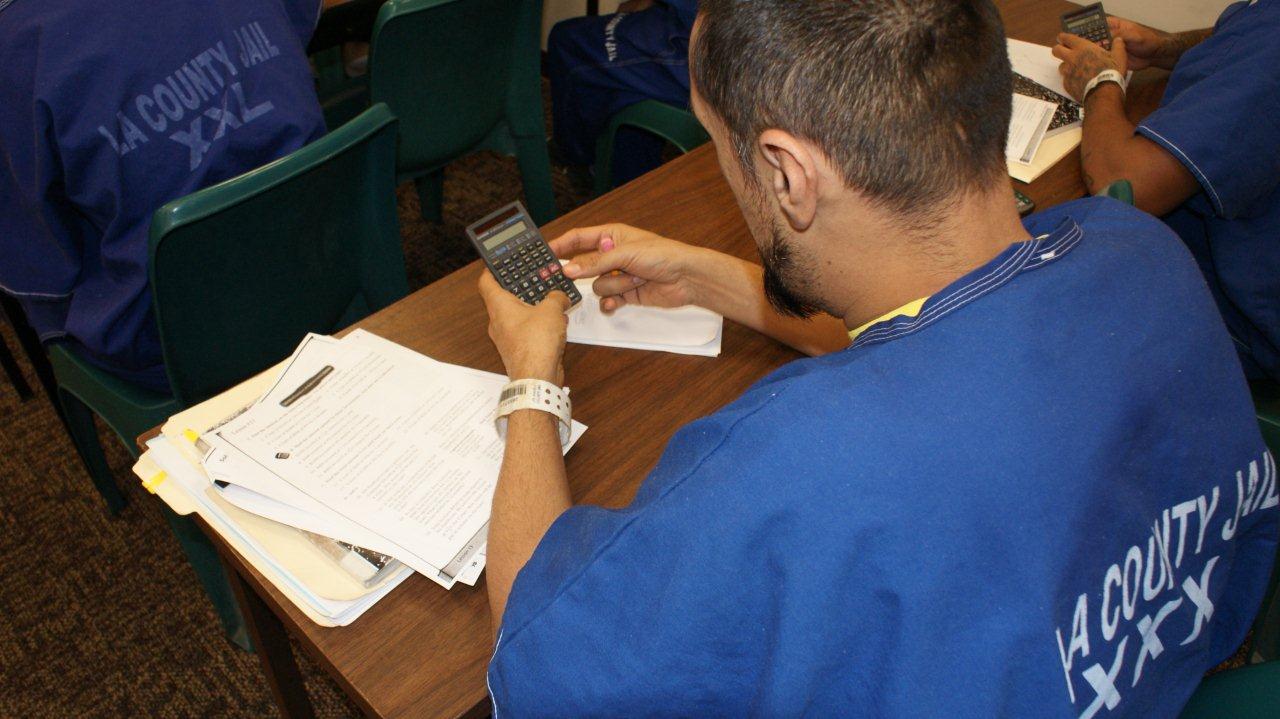

To stretch resources the jail also uses deputies and custody assistants to teach life skill classes, and inmates with subject matter specialties can earn special status to lead courses ranging from real estate investment to kinesiology. Career classes include landscaping, dog grooming, commercial painting and welding. A system that once focused mostly on providing opportunities for General Education Degrees came to understand that most inmates are only a few courses shy of earning actual diplomas, and that a lack of a diploma had limited their employment options. “I see AB 109 as an opportunity,” Choate said. “We have the opportunity to have people here longer and we can actually impact them and complete their education.”

During intake inmates are asked whether they would be interested in educational programs. A second assessment is made to determine which types of programs would improve their chances to succeed in life. Some take academic classes, others enroll in career training. Absent program space jail staff converted dining halls and even borrowed shower stalls for classrooms. “Give them a portable marker board and they’ll turn anything into a classroom,” Choate said. The impact has been immediate. Prison societies that divided inmates by ethnic background or gang affiliation have broken down as educated inmates start to see themselves as human beings first, jail officials say. Inmates of all backgrounds work to tutor each other in classes. The tension level in the jail is reduced and inmate-officer relations have improved. “Look at that pod – you have races that are mixed. That doesn’t happen in the general population,” said Lt. Joseph Badali as he walked through an educational floor of the Twin Towers Correctional Facility during class time. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes.” While the rate of inmate-on-inmate violence is 12 percent annually in the general population, it’s just 2 percent among those in educational programs, jail officials said. So far recidivism (in LA County it’s defined as the re-conviction rate) among the educated is 35 percent, compared with a state prison average of 63 percent. “One of my objectives is to create a safer jail,” Capt. Bornman said. “Evidence is showing that we are having an impact on violence, particularly inmate-on-staff violence. I also believe we are providing meaningful programming that will have a positive effect on the lives of the people who participate.” Not long ago the only interaction between officers and inmates was to bark “Hands in your pockets, right shoulder on the wall, no talking” as they filed out of cells for meals. Now officers in the EBI Bureau counsel inmates on course work and career choices. “When I think of the LA County jail system I think of the word ‘transformation,’” Choate said. “Not all staff buys into programs, but one of the best ways to get your staff on the bus is to take those who are interested, allow them the opportunity to teach and it changes their hearts. Once their hearts change they convert the other staff.” Solomon Brown is serving 6½ years for crimes he committed to support a drug habit. At age 30 he’s now finishing his diploma, taking computer classes and working on art projects – including a collage of pink construction paper hearts that he made for his mother. “I had conditioned myself to certain behaviors that I’m working to change because I have a lot to offer the world,” Brown said. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn.” Raymond H went to juvenile hall at age 16. Now nearing the end of a 5-year sentence for burglary the 33-year-old hopes a high school diploma will help him get an apprenticeship in the trades. “I should have done this a long time ago. It’s helping me get my release together,” he said. “I want to be able to compete in today’s society.”

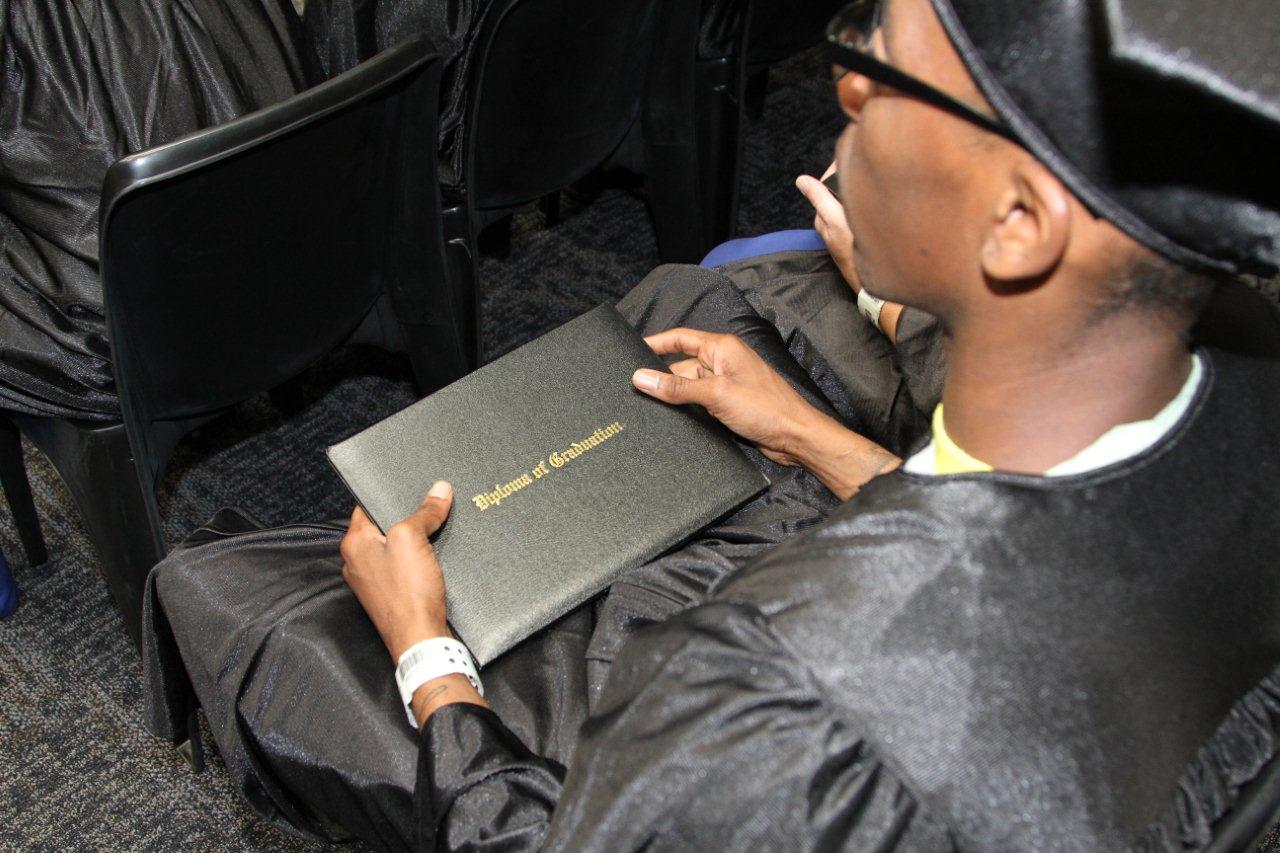

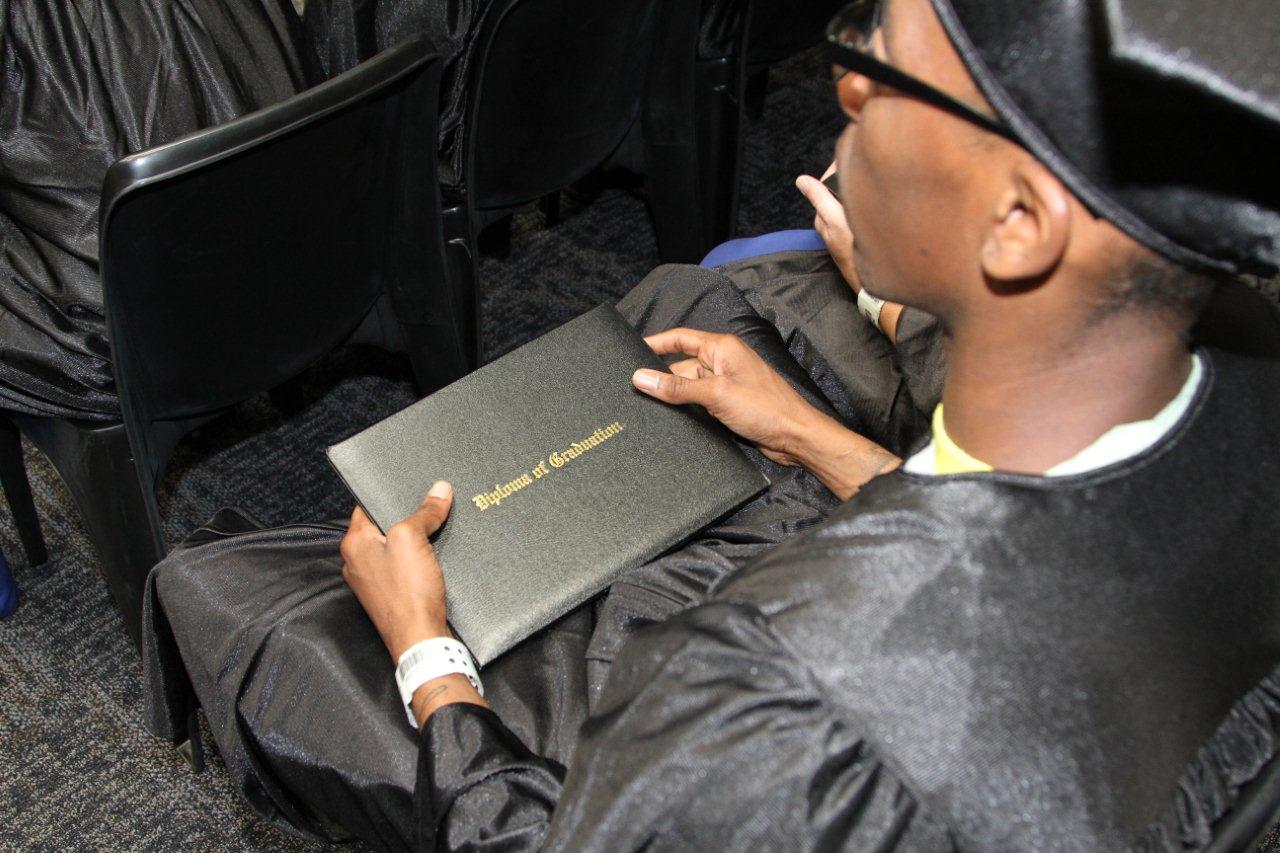

Anna Maria Gonzalez said she believes that the knowledge and confidence she is gaining will keep her from returning to a life of crime. With a mastery of English comprehension she can fill out job applications and have a more stable economic future. It has changed how she sees herself. “My kids are proud of me and I’m embarrassed because they shouldn’t be because I’m in jail. But you know what? I’m proud of myself,” she said. Inmates who complete the programs and secure their high school diplomas are eligible to walk in a graduation ceremony wearing gowns, caps and tassels. Jail officials are hopeful that the education programs can help lower recidivism to the 25-30 percent range. “It is so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Baca said. For more information about educational programs in the Los Angeles County Jails please visit WWW.EBI.LASD.ORG. You can also contact Captain Bornman directly at

mlbornma@lasd.org, or call EBI Bureau at 213-473-2999.

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department “It’s so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Sheriff Leroy Baca of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Jan. 16, 2014. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn,” inmate Solomon Brown, 30. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes,” Lt. Joseph Badali. As women in blue scrubs gather around tables in the Los Angeles County Twin Towers Jail, 45-year-old Anna Maria Gonzalez cracks open a workbook and begins to write. The mother of three grown children left school in Mexico in the sixth grade. She was unable to comprehend written English when she began serving five years for possession of drugs for sale. Now she’s on her way to earning a high school diploma in a cafeteria converted into a classroom. “I feel privileged to be here in this class,” she said. “I heard they didn’t have classes here like this before, and that would be a waste of time for everybody.” In 2011 the Governor’s public safety realignment strategy meant low-level, non-violent offenders and parole violators would serve their terms in county jails, closer to support systems and evidence-based rehabilitative programming designed by officials of the state’s 58 counties. Then-Sheriff Leroy Baca was challenged to find ways to manage thousands of inmates while helping them end the cycle of crime in which many of them where caught. He believes that education is key to ending or slowing recidivism, but when jails held offenders an average of 45 days before sending them to state prisons there wasn’t much he could do. Realignment inspired Baca in 2012 to create a new bureau in his department called Education Based Incarceration (subtitled Creating a Life Worth Living) and he placed Brantley Choate, PhD, in charge of curriculum, and made Capt. Michael Bornman head of the unit. They viewed education as a means for dealing with the tougher caliber of prisoner who could be serving years — instead of weeks — in local jails. “The nature of crime is extraordinarily complex, but education is not complex,” Baca said. “It’s the tool that has advanced civilization from the Dark Ages to now.” The LA jail system contracts with three charter schools to teach inside the six facilities. About 3,000 of the 19,000 inmates housed in the nation’s most populous county jail complex are enrolled in degree and trade programs. The charter schools are funded by the state based on Average Daily Attendance, and costs of the vocational and Life Skills courses are covered by the Inmate Welfare Fund. Teacher Arnold Gamboa trains inmates in basic computer concepts through the New Opportunities Charter School, which is part of the local Centinela Valley Union High School District. He entered the education field as an elementary school teacher but prefers working with his current students. “To see them excited over something they’ve learned is very satisfying to me,” Gamboa said. “I love for them to set a short-term goal in this class and then say to me ‘Mr. Gamboa, I did it!’”

“It’s so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Sheriff Leroy Baca of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Jan. 16, 2014. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn,” inmate Solomon Brown, 30. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes,” Lt. Joseph Badali. As women in blue scrubs gather around tables in the Los Angeles County Twin Towers Jail, 45-year-old Anna Maria Gonzalez cracks open a workbook and begins to write. The mother of three grown children left school in Mexico in the sixth grade. She was unable to comprehend written English when she began serving five years for possession of drugs for sale. Now she’s on her way to earning a high school diploma in a cafeteria converted into a classroom. “I feel privileged to be here in this class,” she said. “I heard they didn’t have classes here like this before, and that would be a waste of time for everybody.” In 2011 the Governor’s public safety realignment strategy meant low-level, non-violent offenders and parole violators would serve their terms in county jails, closer to support systems and evidence-based rehabilitative programming designed by officials of the state’s 58 counties. Then-Sheriff Leroy Baca was challenged to find ways to manage thousands of inmates while helping them end the cycle of crime in which many of them where caught. He believes that education is key to ending or slowing recidivism, but when jails held offenders an average of 45 days before sending them to state prisons there wasn’t much he could do. Realignment inspired Baca in 2012 to create a new bureau in his department called Education Based Incarceration (subtitled Creating a Life Worth Living) and he placed Brantley Choate, PhD, in charge of curriculum, and made Capt. Michael Bornman head of the unit. They viewed education as a means for dealing with the tougher caliber of prisoner who could be serving years — instead of weeks — in local jails. “The nature of crime is extraordinarily complex, but education is not complex,” Baca said. “It’s the tool that has advanced civilization from the Dark Ages to now.” The LA jail system contracts with three charter schools to teach inside the six facilities. About 3,000 of the 19,000 inmates housed in the nation’s most populous county jail complex are enrolled in degree and trade programs. The charter schools are funded by the state based on Average Daily Attendance, and costs of the vocational and Life Skills courses are covered by the Inmate Welfare Fund. Teacher Arnold Gamboa trains inmates in basic computer concepts through the New Opportunities Charter School, which is part of the local Centinela Valley Union High School District. He entered the education field as an elementary school teacher but prefers working with his current students. “To see them excited over something they’ve learned is very satisfying to me,” Gamboa said. “I love for them to set a short-term goal in this class and then say to me ‘Mr. Gamboa, I did it!’”  To stretch resources the jail also uses deputies and custody assistants to teach life skill classes, and inmates with subject matter specialties can earn special status to lead courses ranging from real estate investment to kinesiology. Career classes include landscaping, dog grooming, commercial painting and welding. A system that once focused mostly on providing opportunities for General Education Degrees came to understand that most inmates are only a few courses shy of earning actual diplomas, and that a lack of a diploma had limited their employment options. “I see AB 109 as an opportunity,” Choate said. “We have the opportunity to have people here longer and we can actually impact them and complete their education.”

To stretch resources the jail also uses deputies and custody assistants to teach life skill classes, and inmates with subject matter specialties can earn special status to lead courses ranging from real estate investment to kinesiology. Career classes include landscaping, dog grooming, commercial painting and welding. A system that once focused mostly on providing opportunities for General Education Degrees came to understand that most inmates are only a few courses shy of earning actual diplomas, and that a lack of a diploma had limited their employment options. “I see AB 109 as an opportunity,” Choate said. “We have the opportunity to have people here longer and we can actually impact them and complete their education.”  During intake inmates are asked whether they would be interested in educational programs. A second assessment is made to determine which types of programs would improve their chances to succeed in life. Some take academic classes, others enroll in career training. Absent program space jail staff converted dining halls and even borrowed shower stalls for classrooms. “Give them a portable marker board and they’ll turn anything into a classroom,” Choate said. The impact has been immediate. Prison societies that divided inmates by ethnic background or gang affiliation have broken down as educated inmates start to see themselves as human beings first, jail officials say. Inmates of all backgrounds work to tutor each other in classes. The tension level in the jail is reduced and inmate-officer relations have improved. “Look at that pod – you have races that are mixed. That doesn’t happen in the general population,” said Lt. Joseph Badali as he walked through an educational floor of the Twin Towers Correctional Facility during class time. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes.” While the rate of inmate-on-inmate violence is 12 percent annually in the general population, it’s just 2 percent among those in educational programs, jail officials said. So far recidivism (in LA County it’s defined as the re-conviction rate) among the educated is 35 percent, compared with a state prison average of 63 percent. “One of my objectives is to create a safer jail,” Capt. Bornman said. “Evidence is showing that we are having an impact on violence, particularly inmate-on-staff violence. I also believe we are providing meaningful programming that will have a positive effect on the lives of the people who participate.” Not long ago the only interaction between officers and inmates was to bark “Hands in your pockets, right shoulder on the wall, no talking” as they filed out of cells for meals. Now officers in the EBI Bureau counsel inmates on course work and career choices. “When I think of the LA County jail system I think of the word ‘transformation,’” Choate said. “Not all staff buys into programs, but one of the best ways to get your staff on the bus is to take those who are interested, allow them the opportunity to teach and it changes their hearts. Once their hearts change they convert the other staff.” Solomon Brown is serving 6½ years for crimes he committed to support a drug habit. At age 30 he’s now finishing his diploma, taking computer classes and working on art projects – including a collage of pink construction paper hearts that he made for his mother. “I had conditioned myself to certain behaviors that I’m working to change because I have a lot to offer the world,” Brown said. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn.” Raymond H went to juvenile hall at age 16. Now nearing the end of a 5-year sentence for burglary the 33-year-old hopes a high school diploma will help him get an apprenticeship in the trades. “I should have done this a long time ago. It’s helping me get my release together,” he said. “I want to be able to compete in today’s society.”

During intake inmates are asked whether they would be interested in educational programs. A second assessment is made to determine which types of programs would improve their chances to succeed in life. Some take academic classes, others enroll in career training. Absent program space jail staff converted dining halls and even borrowed shower stalls for classrooms. “Give them a portable marker board and they’ll turn anything into a classroom,” Choate said. The impact has been immediate. Prison societies that divided inmates by ethnic background or gang affiliation have broken down as educated inmates start to see themselves as human beings first, jail officials say. Inmates of all backgrounds work to tutor each other in classes. The tension level in the jail is reduced and inmate-officer relations have improved. “Look at that pod – you have races that are mixed. That doesn’t happen in the general population,” said Lt. Joseph Badali as he walked through an educational floor of the Twin Towers Correctional Facility during class time. “If you occupy their minds you don’t have violence issues. It was a culture change for us, but the buy-in is there because everybody can see the positive changes.” While the rate of inmate-on-inmate violence is 12 percent annually in the general population, it’s just 2 percent among those in educational programs, jail officials said. So far recidivism (in LA County it’s defined as the re-conviction rate) among the educated is 35 percent, compared with a state prison average of 63 percent. “One of my objectives is to create a safer jail,” Capt. Bornman said. “Evidence is showing that we are having an impact on violence, particularly inmate-on-staff violence. I also believe we are providing meaningful programming that will have a positive effect on the lives of the people who participate.” Not long ago the only interaction between officers and inmates was to bark “Hands in your pockets, right shoulder on the wall, no talking” as they filed out of cells for meals. Now officers in the EBI Bureau counsel inmates on course work and career choices. “When I think of the LA County jail system I think of the word ‘transformation,’” Choate said. “Not all staff buys into programs, but one of the best ways to get your staff on the bus is to take those who are interested, allow them the opportunity to teach and it changes their hearts. Once their hearts change they convert the other staff.” Solomon Brown is serving 6½ years for crimes he committed to support a drug habit. At age 30 he’s now finishing his diploma, taking computer classes and working on art projects – including a collage of pink construction paper hearts that he made for his mother. “I had conditioned myself to certain behaviors that I’m working to change because I have a lot to offer the world,” Brown said. “We’re confined, but our minds are always free to learn.” Raymond H went to juvenile hall at age 16. Now nearing the end of a 5-year sentence for burglary the 33-year-old hopes a high school diploma will help him get an apprenticeship in the trades. “I should have done this a long time ago. It’s helping me get my release together,” he said. “I want to be able to compete in today’s society.”  Anna Maria Gonzalez said she believes that the knowledge and confidence she is gaining will keep her from returning to a life of crime. With a mastery of English comprehension she can fill out job applications and have a more stable economic future. It has changed how she sees herself. “My kids are proud of me and I’m embarrassed because they shouldn’t be because I’m in jail. But you know what? I’m proud of myself,” she said. Inmates who complete the programs and secure their high school diplomas are eligible to walk in a graduation ceremony wearing gowns, caps and tassels. Jail officials are hopeful that the education programs can help lower recidivism to the 25-30 percent range. “It is so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Baca said. For more information about educational programs in the Los Angeles County Jails please visit WWW.EBI.LASD.ORG. You can also contact Captain Bornman directly at mlbornma@lasd.org, or call EBI Bureau at 213-473-2999.

Anna Maria Gonzalez said she believes that the knowledge and confidence she is gaining will keep her from returning to a life of crime. With a mastery of English comprehension she can fill out job applications and have a more stable economic future. It has changed how she sees herself. “My kids are proud of me and I’m embarrassed because they shouldn’t be because I’m in jail. But you know what? I’m proud of myself,” she said. Inmates who complete the programs and secure their high school diplomas are eligible to walk in a graduation ceremony wearing gowns, caps and tassels. Jail officials are hopeful that the education programs can help lower recidivism to the 25-30 percent range. “It is so remarkable to see human intelligence triumph over bad behavior,” Baca said. For more information about educational programs in the Los Angeles County Jails please visit WWW.EBI.LASD.ORG. You can also contact Captain Bornman directly at mlbornma@lasd.org, or call EBI Bureau at 213-473-2999.  Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department

Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department